Yesterday, July 25, was a big day. Ironhide Games released the long-awaited fifth edition of their tower-defence game ‘Kingdom Rush’. I bought it as soon as it launched and completed its primary campaign in one sitting of several hours. Called ‘Alliance’, the game combines the gameplay of ‘Kingdom Rush: Vengeance’ and Ironhide’s ‘Junkworld’, together with aspects of ‘Legends of Kingdom Rush’. The game also continues a long storyline that began with the first ‘Kingdom Rush’ game, released in 2011, and last updated in ‘Vengeance’. For what it’s worth, it’s a good story, too.

In ‘Kingdom Rush: Origins’, Ironhide introduced Vez’nan as a powerful wizard who becomes corrupted by a gem called the Tear of Elynie to become a malevolent power threatening the kingdom of Linirea. In the games that followed, heroes and towers from several parts of the kingdom, ultimately including King Denas, were tasked with defeating Vez’nan and his allies. In ‘Vengeance’, Vez’nan returned to exact revenge against King Denas — or so it seemed. ‘Alliance’ describes Denas’s return as well as Vez’nan’s efforts against a greater evil called the Overseer, who is also the ultimate boss in ‘Legends of Kingdom Rush’.

I love tower-defence games and among them ‘Kingdom Rush’ is my favourite by far. I own all editions of it as well as have unlocked most towers and heroes in each one. At more than a few points during a work day, I like to break one of these games out for a quick and hairy skirmish or — time permitting — a full-on campaign on a high difficulty setting.

But while I like to play as often as I can, tower-defence doesn’t fit all moods. I have 13 games on my phone: the five ‘Kingdom Rush’ games, ‘Junkworld’, ‘Monument Valley’ I and II (and the expansion packs), ‘Loop’, ‘1010!’, ‘Idle Slayer’, ‘Rytmos’, and ‘Lost in Play’. They’re all great but I’d single out ‘Idle Slayer’, ‘Loop’, and ‘Monument Valley’ for particular praise.

‘Idle Slayer’ is a top-notch incremental game (a.k.a. idle game): the game will continue irrespective of whether you interact with the player-character, the player-character can’t perish, and gameplay is restricted to tapping on the screen to make the character jump. The whole point is to slay monsters — which the character will if she/flies runs into them, automatically pulling out an omnipotent sword when she gets close — and collect slayer points and to pick up coins and gems, which the character also does if she runs/flies into them. ‘Idle Slayer’ thus eliminates the player (you, me, etc.) having to be challenged in order to reap rewards. It’s just a matter of time, although occasional bursts of speed and character abilities purchased with slayer points can make things exciting.

I agree with what journalist Justin Davis wrote in 2013:

“Idle games seem perfectly tuned to provide a never-ending sense of escalation. They’re intoxicating because upgrades or items that used to seem impossibly expensive or out of reach rapidly become achievable, and then trivial. It’s all in your rearview mirror before you know it, with a new set of crazy-expensive upgrades ahead. The games are tuned to make you feel both powerful and weak, all at once. They thrive on an addictive feeling of exponential progress.”

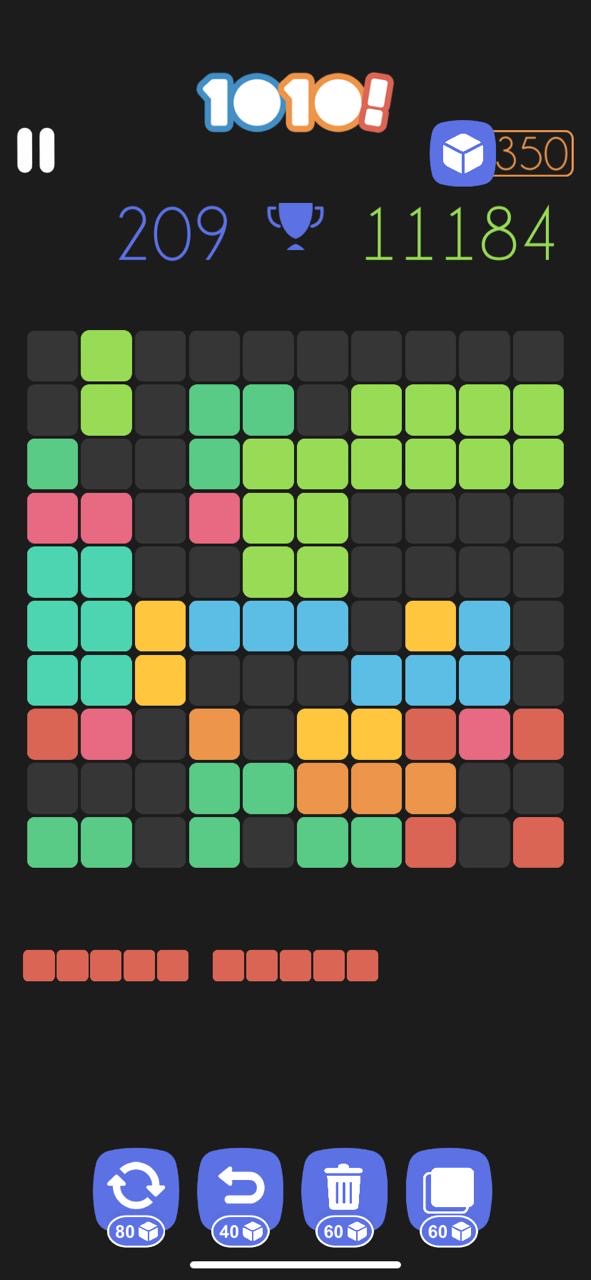

Right now, this is where I’m at: 209 decillion coins in my kitty and racking up 110 octillion coins per second, plus whatever I pick up as I keep running…

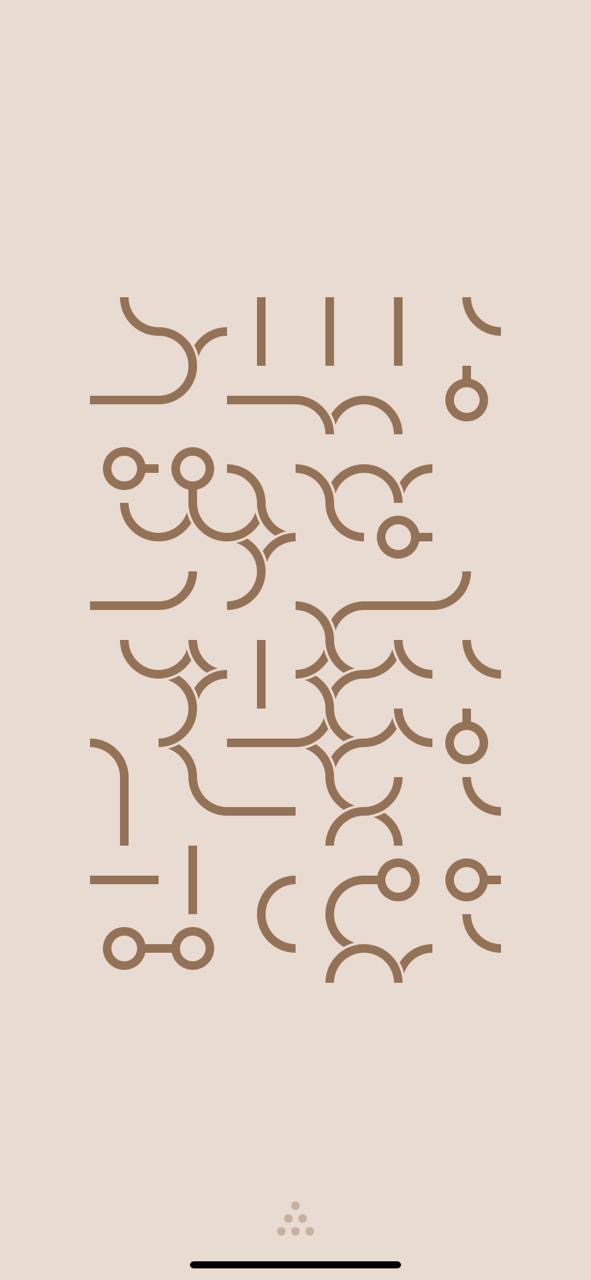

Second is the amazing ‘Loop’, an endless series of puzzles in each of which your task is to link up some open-ended elements on a screen such that they form a large closed loop. You can tap on each element to rotate it; when the open ends of two elements line up in this way, they link up. The game is minimalist: each level has a plain monotone background and elements of a contrasting colour, and there’s beautiful, low-key instrumental music to accompany your thoughts. ‘Loop’ is the game to get lost in. I’ve played more than 3,500 levels so far and look forward every day to the next one.

Third comes ‘Monument Valley’, but in no particular order because it’s the game I love the most. I don’t play it as often as I play ‘Kingdom Rush’, ‘Idle Slayer’ or ‘Loop’ because its repeatability is low — but it’s the game that redefined for a younger and less imaginative me what a smartphone product could look and feel like when you play it. ‘Monument Valley’ is an ode to the work of the Dutch artist MC Escher, famed for his depiction of impossible objects that toy with the peculiarities of human visual perception. The player-character is a young lady named Ida navigating a foreboding but also enchanting realm whose structures and vistas are guided by the precepts of a mysterious “sacred geometry”. The game’s visuals are just stunning and, as with ‘Loop’, there’s beautiful music to go with. The objects on the screen whose geometries you change to create previously impossible paths for Ida take time to move around, which means you can’t rush through levels. You have to wait, and you have to watch. And ‘Monument Valley’ makes that a pleasure to do.

It should be clear by now that I love puzzles, and ‘1010!’ is perhaps the most clinical of the lot. It’s Tetris in pieces: you have a 10 x 10 grid of cells that you can fill with shapes that the game presents to you in sets of three. Once you’ve placed all three on the grid, you get the next three; once a row or a column is filled with cells, it empties itself; and once you can no longer fit new shapes in the grid, it’s game over. ‘1010!’ takes up very little of your cognitive bandwidth, which means you have something to do that distracts you enough to keep you from feeling restless while allowing you to think about something more important at the same time.

‘Rytmos’ and ‘Lost in Play’ are fairly new: I installed them a couple weeks ago. ‘Rytmos’ is just a smidge like ‘Loop’ but richer with details and, indeed, knowledge. You link up some nodes on a board in a closed loop; each node is a musical instrument that, when it becomes part of the loop, plays a beat depending on its position. Suddenly you’re making music. There are multiple ‘planets’ in the game and each one has multiple puzzles involving specific instruments. You learn something and you feel good about it. It’s amazing. I’ve only played a few minutes of ‘Lost in Play’ thus far, and I’m looking forward to more because it seems to be of a piece with ‘Monument Valley’, from the forced-slow gameplay to the captivating visuals.

Aside from these games, I also play ‘Entanglement’ in the browser and ‘Factorio’ on my laptop. ‘Factorio’ is the motherlode, an absolute beast of a game for compulsive puzzle-solvers. In the game, you’re an engineer in the future who’s crash-landed on an alien planet and you need to build a rocket to get off of it. The gameplay is centred on factories, where you craft the various pieces required for more and more sophisticated components. In parallel, you mine metals, pump crude oil, extract uranium, and dig up coal; you smelt, refine, and burn them to get the parts required to build as well as feed the factories; you conduct research to develop and enhance automation, robotics, rocketry, and weapons; you build power plants and transmission lines, and deal with enormous quantities of waste; and you defend your base from the planet’s native life, a lone species of large, termite-like creatures.

I’ve been playing a single game for three years now. There’s no end in sight. Sometimes, when ‘Factorio’ leaves me enough of my brain to think about other things, I gaze with longing as if out of a small window at a world that has long passed me by…