Researchers from the University of Delaware have developed a chemical reaction that can break polyester in clothing down to a simpler compound that can be used to make more clothes. The reaction also spares cotton and nylon, allowing them to be recovered separately from clothing that uses a mix of fibres. Most of all, given sufficient resources, the reaction reportedly takes only 15 minutes from start to finish, which the researchers have touted as a significant achievement because I believe the prevailing duration for other chemical material-recovery processes in the textile industry is in the order of days, and have said they hope to be able to bring it down to a matter of seconds.

The team’s paper and its coverage in the popular press also advance the narrative that the finding could be a boon for the textile industry’s monumental waste problem, especially in economically developing and developed regions. This is obviously the textile industry’s analogue of carbon capture and storage (CCS) technologies, whereby certain technical machinations remove carbon out of the atmosphere and other natural reservoirs and sequester it in human-made matrices for decades or even centuries. The problem with CCS is also the problem with the chemical recycling process described in the new study: unless the state institutes policies and helps effect cultural changes in parallel that discourage consumption, encourage reuse, and lower emissions, removing contaminants from the environment will only create the impression that there is now more room to pollute, so the total effective carbon pollution will increase. This is not unlike trying to reduce motor vehicle traffic by building more roads: cities simply acquire more vehicles with which to fill the newly available motorway space.

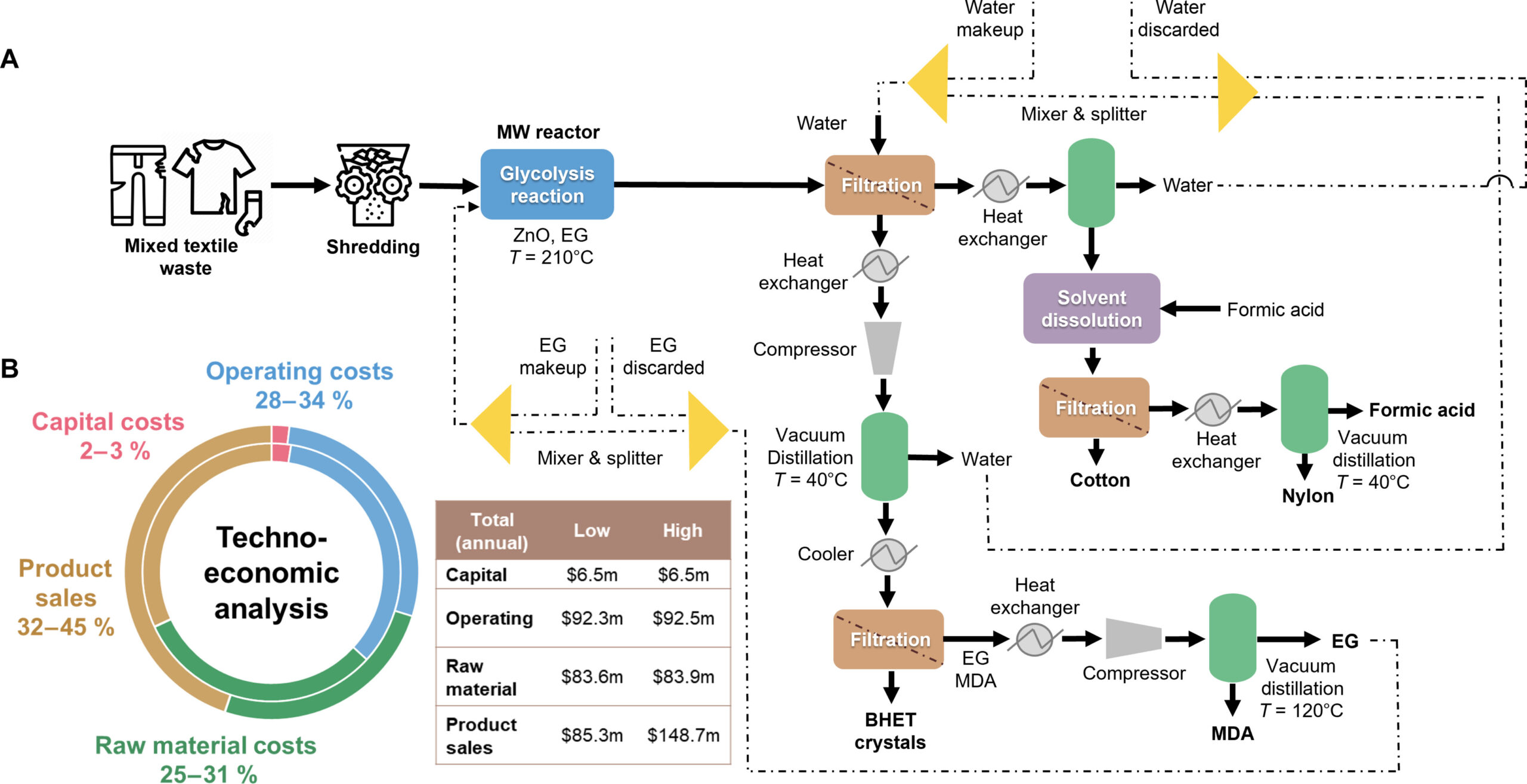

All this said, however, there is one more thing to be concerned about vis-à-vis the 15-minute chemical recovery technique. In their paper, the researchers described a “techno-economic assessment” they undertook to understand the “economic feasibility” of their proposed solution to the textile waste problem. Their analysis flowchart is shown below, based on a “textile feed throughput of 500 kg/hour”. A separate table (available here) specifies the estimated market value of textile components — polyester, nylon, cotton, and 4,4′-methylenedianiline (MDA) — after they have been recovered from the 15-minute reaction’s output and processed a bit. They found their process is more economically feasible, achieving a profitability index of 1.29 where 1 is the breakeven point, when the resulting product sales amount to $148.7 million. I don’t know where the latter figure comes from; if it doesn’t have a sound basis and is arbitrary, the ‘1.29’ figure would be arbitrary too. The same goes for their ‘low sales’ scenario in which the profitability index is 0.95 if sales amount to $85.3 million.

Source: DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.ado6827

Importantly, all these numbers presume demand for recycled clothes, which I assume is far more limited (based on my experiences in India) than the demand for new clothes. In fact the researchers’ paper begins by blaming fast fashion for the “rising demand for textiles and [their] shorter life span compared to a generation ago”. Fast fashion is a volume business predicated among other things on lower costs. (Did you hear about the mountain of clothes that went up in flames in the middle of the Atacama desert in 2022 because it was cheaper to let them go that way?) Should fast-fashion’s practices be accounted for in the techno-economic assessment, I doubt its numbers would still stand. They certainly won’t if implemented in the poorer countries to which richer ones have been exporting both textile manufacturing and disposal. Second, the profitability indices presume continuing, if not increasing, demand for new clothes, which is of course deeply problematic: demand untethered from their socio-economic consequences is what landed us in the present soup. That it should stay this way or further increase in order to sustain a process that “holds the potential to achieve a global textile circularity rate of 88%” is a precarious proposition because it risks erecting demand as the raison d’être of sustainability.

Finally, militating against solutions like CCS and this chemical recovery technique because they aren’t going to be implemented within the right policy and socio-cultural frameworks is reasonable even if the underlying technologies have matured completely (they haven’t in this case but let’s set that aside). On the flip side, we need to push governments to design and implement the frameworks asap rather than delay or deny the use of these technologies altogether. The pressures of climate change have shortened deadlines and incentivised speed. Yet business people and industrialists have imported far too many such solutions into India, where their purported benefits have seldom come to fruition — especially in their intended form — even as they have had toxic consequences for the people depending on these industries for their livelihoods, for the people living around these facilities, and, importantly, for people involved in parts of the value chain that come into view only when we account for externalised costs. A few illustrative examples are sewage treatment plants, nuclear reactors, hazardous waste management, and various ore-refining techniques.

In all, making the climate transition at the expense of climate justice is a fundamentally stupid strategy.

Featured image: People sort through hundreds of tonnes of clothing in an abandoned factory in Phnom Penh, November 22, 2020. Credit: Francois Le Nguyen/Unsplash.