At 9 pm India time on April 7, physicists at an American research facility delivered a shot in the arm to efforts to find flaws in a powerful theory that explains how the building blocks of the universe work.

Physicists are looking for flaws in it because the theory doesn’t have answers to some questions – like “what is dark matter?”. They hope to find a crack or a hole that might reveal the presence of a deeper, more powerful theory of physics that can lay unsolved problems to rest.

The story begins in 2001, when physicists performing an experiment in Brookhaven National Lab, New York, found that fundamental particles called muons weren’t behaving the way they were supposed to in the presence of a magnetic field. This was called the g-2 anomaly (after a number called the gyromagnetic factor).

An incomplete model

Muons are subatomic and can’t be seen with the naked eye, so it could’ve been that the instruments the physicists were using to study the muons indirectly were glitching. Or it could’ve been that the physicists had made a mistake in their calculations. Or, finally, what the physicists thought they knew about the behaviour of muons in a magnetic field was wrong.

In most stories we hear about scientists, the first two possibilities are true more often: they didn’t do something right, so the results weren’t what they expected. But in this case, the physicists were hoping they were wrong. This unusual wish was the product of working with the Standard Model of particle physics.

According to physicist Paul Kyberd, the fundamental particles in the universe “are classified in the Standard Model of particle physics, which theorises how the basic building blocks of matter interact, governed by fundamental forces.” The Standard Model has successfully predicted the numerous properties and behaviours of these particles. However, it’s also been clearly wrong about some things. For example, Kyberd has written:

When we collide two fundamental particles together, a number of outcomes are possible. Our theory allows us to calculate the probability that any particular outcome can occur, but at energies beyond which we have so far achieved, it predicts that some of these outcomes occur with a probability of greater than 100% – clearly nonsense.

The Standard Model also can’t explain what dark matter is, what dark energy could be or if gravity has a corresponding fundamental particle. It predicted the existence of the Higgs boson but was off about the particle’s mass by a factor of 100 quadrillion.

All these issues together imply that the Standard Model is incomplete, that it could be just one piece of a much larger ‘super-theory’ that works with more particles and forces than we currently know. To look for these theories, physicists have taken two broad approaches: to look for something new, and to find a mistake with something old.

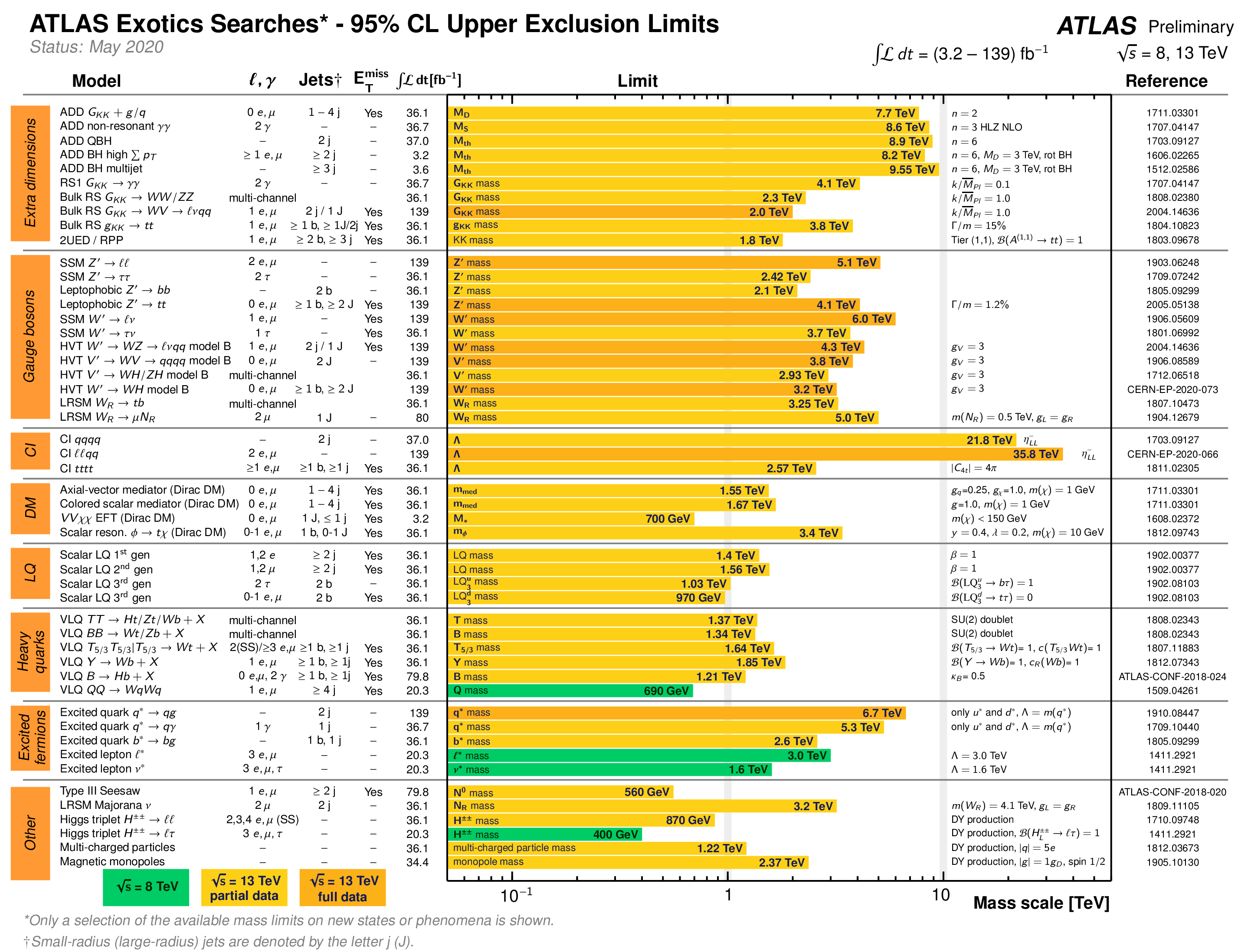

For the former, physicists use particle accelerators, colliders and sophisticated detectors to look for heavier particles thought to exist at higher energies, and whose discovery would prove the existence of a physics beyond the Standard Model. For the latter, physicists take some prediction the Standard Model has made with a great degree of accuracy and test it rigorously to see if it holds up. Studies of muons in a magnetic field are examples of this.

According to the Standard Model, a number associated with the way a muon swivels in a magnetic field is equal to 2 plus 0.00116591804 (with some give or take). This minuscule addition is the handiwork of fleeting quantum effects in the muon’s immediate neighbourhood, and which make it wobble. (For a glimpse of how hard these calculations can be, see this description.)

Fermilab result

In the early 2000s, the Brookhaven experiment measured the deviation to be slightly higher than the model’s prediction. Though it was small – off by about 0.00000000346 – the context made it a big deal. Scientists know that the Standard Model has a habit of being really right, so when it’s wrong, the wrongness becomes very important. And because we already know the model is wrong about other things, there’s a possibility that the two things could be linked. It’s a potential portal into ‘new physics’.

“It’s a very high-precision measurement – the value is unequivocal. But the Standard Model itself is unequivocal,” Thomas Kirk, an associate lab director at Brookhaven, had told Science in 2001. The disagreement between the values implied “that there must be physics beyond the Standard Model.”

This is why the results physicists announced today are important.

The Brookhaven experiment that ascertained the g-2 anomaly wasn’t sensitive enough to say with a meaningful amount of confidence that its measurement was really different from the Standard Model prediction, or if there could be a small overlap.

Science writer Brianna Barbu has likened the mystery to “a single hair found at a crime scene with DNA that didn’t seem to match anyone connected to the case. The question was – and still is – whether the presence of the hair is just a coincidence, or whether it is actually an important clue.”

So to go from ‘maybe’ to ‘definitely’, physicists shipped the 50-foot-wide, 15-tonne magnet that the Brookhaven facility used in its Muon g-2 experiment to Fermilab, the US’s premier high-energy physics research facility in Illinois, and built a more sensitive experiment there.

The new result is from tests at this facility: that the observation differs from the Standard Model’s predicted value by 0.00000000251 (give or take a bit).

The Fermilab results are expected to become a lot better in the coming years, but even now they represent an important contribution. The statistical significance of the Brookhaven result was just below the threshold at which scientists could claim evidence but the combined significance of the two results is well above.

Potential dampener

So for now, the g-2 anomaly seems to be real. It’s not easy to say if it will continue to be real as physicists further upgrade the Fermilab g-2’s performance.

In fact there appears to be another potential dampener on the horizon. An independent group of physicists has had a paper published today saying that the Fermilab g-2 result is actually in line with the Standard Model’s prediction and that there’s no deviation at all.

This group, called BMW, used a different way to calculate the Standard Model’s value of the number in question than the Fermilab folks did. Aida El-Khadra, a theoretical physicist at the University of Illinois, told Quanta that the Fermilab team had yet to check BMW’s approach, but if it was found to be valid, the team would “integrate it into its next assessment”.

The ‘Fermilab approach’ itself is something physicists have worked with for many decades, so it’s unlikely to be wrong. If the BMW approach checks out, it’s possible according to Quanta that just the fact that two approaches lead to different predictions of the number’s value is likely to be a new mystery.

But physicists are excited for now. “It’s almost the best possible case scenario for speculators like us,” Gordan Krnjaic, a theoretical physicist at Fermilab who wasn’t involved in the research, told Scientific American. “I’m thinking much more that it’s possibly new physics, and it has implications for future experiments and for possible connections to dark matter.”

The current result is also important because the other way to look for physics beyond the Standard Model – by looking for heavier or rarer particles – can be harder.

This isn’t simply a matter of building a larger particle collider, powering it up, smashing particles and looking for other particles in the debris. For one, there is a very large number of energy levels at which a particle might form. For another, there are thousands of other particle interactions happening at the same time, generating a tremendous amount of noise. So without knowing what to look for and where, a particle hunt can be like looking for a very small needle in a very large haystack.

The ‘what’ and ‘where’ instead come from different theories that physicists have worked out based on what we know already, and design experiments depending on which one they need to test.

Into the hospital

One popular theory is called supersymmetry: it predicts that every elementary particle in the Standard Model framework has a heavier partner particle, called a supersymmetric partner. It also predicts the energy ranges in which these particles might be found. The Large Hadron Collider (LHC) in CERN, near Geneva, was powerful enough to access some of these energies, so physicists used it and went looking last decade. They didn’t find anything.

Other groups of physicists have also tried to look for rarer particles: ones that occur at an accessible energy but only once in a very large number of collisions. The LHC is a machine at the energy frontier: it probes higher and higher energies. To look for extremely rare particles, physicists explore the intensity frontier – using machines specialised in generating collisions.

The third and last is the cosmic frontier, in which scientists look for unusual particles coming from outer space. For example, early last month, researchers reported that they had detected an energetic anti-neutrino (a kind of fundamental particle) coming from outside the Milky Way participating in a rare event that scientists predicted in 1959 would occur if the Standard Model is right. The discovery, in effect, further cemented the validity of the Standard Model and ruled out one potential avenue to find ‘new physics’.

This event also recalls an interesting difference between the 2001 and 2021 announcements. The late British scientist Francis J.M. Farley wrote in 2001, after the Brookhaven result:

… the new muon (g-2) result from Brookhaven cannot at present be explained by the established theory. A more accurate measurement … should be available by the end of the year. Meanwhile theorists are looking for flaws in the argument and more measurements … are underway. If all this fails, supersymmetry can explain the data, but we would need other experiments to show that the postulated particles can exist in the real world, as well as in the evanescent quantum soup around the muon.

Since then, the LHC and other physics experiments have sent supersymmetry ‘to the hospital’ on more than one occasion. If the anomaly continues to hold up, scientists will have to find other explanations. Or, if the anomaly whimpers out, like so many others of our time, we’ll just have to put up with the Standard Model.

Featured image: A storage-ring magnet at Fermilab whose geometry allows for a very uniform magnetic field to be established in the ring. Credit: Glukicov/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0.

The Wire Science

April 8, 2021